嘉央諾布:回憶第一位讚贊步行者

1988年10月的一天晚上,已是深夜時分,我被一通來自美國的電話吵醒。我當時住在日本,教授英文,偶爾為日本時報寫書評。之前幾年,我在西藏流亡社區 的二十年工作才剛剛結束--我本來是西藏話劇團(Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, TIPA)的團長,為了一兩齣戲中別人所認為的不敬之處而遭到解雇(還加上一幫暴力的摩洛甘濟(McLeod Ganj)(譯按1)的暴民的幫助 )。

那個著急的聲音用藏語問我:「嘉央諾布,嘉央諾布,你聽得到我嗎?我是圖登晉美諾布。」我一時之間不知道這個名字是誰,然後恍然大悟,知道他就是塔澤仁波切,達賴喇嘛的大哥。「是的,仁波切我聽得到。你好嗎?」

「嘉央諾布,嘉央諾布,你知道發生什麼事了嗎?」

「什麼事,仁波切?」

「他們放棄了我們的讓贊。」

「仁波切,你在說什麼?」

「嘉瓦仁波切在這個名叫史特拉斯堡的地方作了一個聲明‧‧‧」(譯按2)

然後他告訴我所發生的事情。

我跟達賴喇嘛的家人並不親近,而我也花了一點時間才明白為什麼塔澤仁波切跟我聯絡。原因大概是因為我之前在《西藏評論》發表的一些文章,我經常性地分析並 且譴責西藏政府的政策,認為噶廈降低了西藏獨立的重要性,好與中共和解。我最後在那裏發表的文章是一篇分成兩部份的文章(〈在邊緣之上〉,1986年10 月號、11月號),文中警告愈來愈多漢人移民至西藏的危險。我強調唯一處理這個危機的辦法,不是安撫北京,而是積極地不鼓勵在西藏的貿易、觀光與投資,讓 西藏不穩。在鄧小平自由化的早年,是有機會做出這樣的事情的。當然,噶廈根本忽視我的報告。一兩個英國讀者指控我,說我破壞了漢藏之間的美好新關係。

「你會怎麼做?」仁波切在談話的最後問我。

我能說什麼?我告訴他我不知道;我不處於可以做事的位置上。

我想我的答案讓他失望,然而那一次的談話開啟了我們的友誼。我們雙方都有一點在情緒上依賴這份友誼。因為那些支持獨立的人在流亡社區裏變成愈來愈邊緣化, 而且任何對於中間道路有所懷疑的人,都很容易受到「反對」達賴喇嘛的指控。所以即使是你剛好住在地球的另一端,你也從這種友誼之中尋求力量,不管距離多 遠,沒有放棄讓贊的人彼此互相支持。

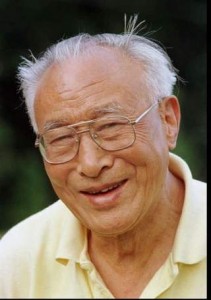

當時的仁波切早已過了年富力強的年紀,事實上,他是在七十三歲時,靠著勞倫斯‧葛爾斯坦(Lawrence Gerstein)的幫助,創辦了國際西藏獨立運動,並且領導了幾次的獨立步行活動,行踪遍及美國與加拿大。我在那些年頭裏住在達蘭薩拉,編輯著西藏新聞 《人民》(Mangtso),每次看到仁波切步行的照片,都很令人精神振奮,他很有精神地邁著步伐,反戴著一頂白色的棒球帽,告訴美國:西藏是一個獨立的 國家,而美國人應該支持西藏。

他似乎總是以笑容做出這樣的聲明。仁波切不是一個神情嚴肅咬牙切齒的民族主義者。他對於讓贊的信念並不是來自於對中國人民的憎恨,或者某種超級愛國的教條 或哲學,而僅僅只是出於他對中國之於西藏真正的意圖沒有任何幻想。仁波切相信西藏需要獨立,不是為了某種高尚的意識形態原因,而是一種基本的條件,因為藏 人的生存--他們的語言、他們的文化、甚至他們的宗教都仰賴獨立才能獲得保證。仁波切很確定,沒有其他的辦法了。

我感覺,仁波切的想法之中,對這一點思考的明晰,源自於他在當塔爾寺主持時,在安多遭遇的共產黨領袖,這一幫人都是粗鄙、自以為是、狡詐而又喜好殺人的人 --他們都是非常野蠻血腥的中國內戰的產物、毫無人性的人。仁波切在他的自傳《西藏是我的國家》裏很準確地描寫他們。左翼的宣傳家,如埃德加‧史諾,給我 們一種中國共產黨的幹部與官員都是理想化的農民改革者,懷抱著道家聖賢的理想,但任何知道一點中國共產黨的歷史的人就會知道紅軍之中,有許多人都是前軍閥 的手下、傭兵、土匪、地頭蛇等等。仁波切也目睹了他們如何殲滅塔爾寺附近,魯沙爾鎮(位於今日青海省西寧市湟中縣境內)的穆斯林回人。當紅軍屠殺囊拉(Nangra), 霍莫卡(Hormukha,應寫作Hormokha)的安多人,並且開始他們對果洛人的種族殲滅戰之時,仁波切人就在安多。

在安多,共產黨人並沒有試圖使用狡計與甜言蜜語來贏得人心。大概是因為他們覺得青海早已是囊中之物,所以不必多費精神。另一方面,他們對衛藏的入侵,結果卻相當不確定,所以共產黨人慎選他們在拉薩與昌都的代表,確定他們的人選都是表面上看起來很愉快、很有口才的人物。

聖尊達賴喇嘛所遇到、並且有來往的第一批共黨官員都是親切有魅力、處世圓滑的人物,如平措汪傑、或者像劉格平這樣死硬的共產主義信徒(譯註3), 這兩位就是向達賴喇嘛傳揚馬克思列寧主義、共產黨歷史與蘇聯民族政策的人。平措汪傑在他的自傳裏提到,「達賴喇嘛對學習著共產主義的各種層面非常熱心,而 我想我對他的思考有所影響。即使到今日,他有時候還說他是一半佛教徒,一半馬克思主義者。」我們必須謹記的是,聖尊當時非常年輕,還在容易受到他人影響的 年紀。他長期牢固的信念,認為可以就西藏問題與中國領導人達成某種諒解,大概是受到這種早年的經歷所影響。

但塔澤仁波切當時已經成年了,他比聖尊大十三歲,而他與共產黨人的交往經驗,使他堅信中國對西藏的意圖是邪惡的。仁波切自己也能夠偽裝,他想辦法裝出對於 共產黨人的提案有所接受的樣子。他們於是決定派他到拉薩去贏取達賴喇嘛的信任。仁波切描述與他接觸的共黨領袖不可置信的粗糙方法:如果他可以說服達賴喇 嘛,讓西藏政府放棄抵抗中國軍隊的入侵的話,他們答應要聘任他為西藏「省長」 (chikyap) 。他們甚至還暗示他,如果達賴喇嘛太過礙手礙腳的話,他們就會想辦法處理掉他,而仁波切說不定也可以自己動手,「‧‧‧以達到(他當上西藏省長)的目 的」。

仁波切在人民解放軍入侵之前來到拉薩,告訴他弟弟每件事。他的忠告也許就是促成年輕的達賴喇嘛與西藏內閣在昌都淪陷之後,決定離開拉薩。當西藏政府與達賴喇嘛決定暫時在春丕谷(Chumbi valley)的錯模(今日西藏自治區日喀則亞東縣)住 下來,仁波切決定他要繼續前往印度。一旦到了印度之後,他的老朋友,帝洛巴仁波切與他連絡。他告訴塔澤,他已經透過自由亞洲委員會(一個CIA的附屬機 構)安排他前往美國。帝洛巴仁波切是地位非常崇高的蒙古喇嘛,曾經經歷過史達林的整肅,並且在1949年受約翰霍普金斯大學的邀請前往任教。而運作此事成 功的美國人是一位傑出的東方學者,歐文‧拉鐵摩爾(Owen Lattimore),當時他是美國國務院遠東事務部門的重要顧問。很諷刺的是,這位幫助蒙古高僧、又間接幫助塔澤仁波切逃離共產黨迫害的人,居然會在後 來變成麥卡錫參議員反共運動所針對的主要對象,並且面臨作為「高級蘇維埃間諜」的虛偽指控。

仁波切在美國一開始並不順利,他的健康不佳,又不會說英語,也沒有錢。但他慢慢地學習著英語(在加州柏克萊),甚至在印度政府無法更新他的居留證而美國政 府又不給他庇護時,停留在日本寺院幾年,期間學會了日語。CIA當時因為西藏的代表與北京簽訂了十七條協議,而達賴喇嘛也返回了拉薩,對塔澤仁波切已經失 去了原來的興趣。最後,大概三年之後,他在美國基督教世界救濟會(Church World Service)的朋友,為仁波切取得返回美國的許可。他在哥倫比亞大學向幾個學生教授沒有學分的藏語課程,因此賺取一點微薄的收入,而他的僕人頓珠嘉贊 則必須到工廠裏去作工。我從他的自傳裏得到的印象是,仁波切在他小小的紐約公寓裏每天晚上都在「‧‧‧根據傳統的西藏食譜」煮湯(很有可能是湯庫 (thinkhuk),是一種羊肉或氂牛肉與青棵熬煮加鹽的美味湯)。

當時,西藏與共產黨人正處於蜜月時期,許多商人、喇嘛、寺院、貴族與堯西(譯註4)都 對中國人帶到西藏四處散布的銀元十分高興。他在他的自傳裏非常坦白地提到,許多試圖勸仁波切回家的舊識裏,包括他自己的親戚在內。但仁波切相信這些得來容 易的錢財,與共產黨人的親切都只是過渡時期而已,很快對方就會露出真面目。他的弟弟,嘉樂頓珠,稍早曾經在南京的國民黨學校裏讀書,對於共產黨人也不太信 任,也從中國逃往印度。

當達賴喇嘛在1956年前往印度參加菩提伽耶的慶典時,仁波切立刻飛往印度,與嘉樂頓珠一起,試圖勸服弟弟在印度尋求庇護。其他的流亡藏人領袖,如前總理 (首席噶倫)魯康娃,也懇求達賴喇嘛不要回西藏去。但到了最後,達賴喇嘛諮詢了國家的護法神。達賴喇嘛在《流亡中的慈悲》中提到,當時神巫對魯康娃在場十 分生氣,然而魯康娃還是拒絕離開。老貴族魯康娃警告達賴喇嘛,「當人絕望時,他們就尋問眾神。而當神絕望時,他們就會說謊。」然而達賴喇嘛還是返回了拉 薩。

非常失望的塔澤仁波切飛回紐約。但此時,東藏各地的反抗已經全面爆發,而仁波切與美國國務院保持經常性的連繫。他也重新與CIA建立了連繫。在接受我的專 訪時,他說他後來把所有的連絡資料都轉交給他的弟弟。他並沒有明確地說出來,但我假定他覺得嘉樂頓珠對於這種密謀策動比較在行,而且又富有外交手腕,可以 充份利用與美國政府的連繫來促進西藏的利益。

仁波切也幫忙在塞班島訓練第一批的藏人游擊隊(包括阿塔、洛澤、嘉洛旺堆等等),他的角色是翻譯。仁波切與卡爾梅克的高僧格西旺傑(Geche Wangyal)也幫忙CIA發明了一套電碼系統,以指稱那些藏語字彙中沒有的事物,並且創造了一套有關於現代戰爭與情報收集的精確書寫系統。仁波切與格 西旺傑也參與了寫作游擊戰、破壞戰等技巧的手冊。

仁波切懂多種語言:藏文、蒙文、日文、中文、英文,還有他故鄉西寧的方言,顯示他作為學者的天賦,也許他也覺得戰事與間諜戰的種種,與他的本性並不相符, 他還是回到了學術界。但也開始為西藏難民組織救濟工作,靠著他在美國基督教世界救濟會(Church World Service)朋友的幫忙。

仁波切在美國自然史博物館開啟了藏學研究的計畫,也開始在印第安那大學發展出類似的計畫,後者他並且獲得了教職。1965年他開始在那裏教書,他的一個學生告訴我:「他很容易就可以吸引學生來上他的課。」

這位高僧、格魯教派最重要寺院之一的主持、達賴喇嘛的大哥,最讓我覺得有趣的地方是,他對於教授佛法或者成立佛法中心並不感興趣,反而是想讓世界知道西藏 的文化、歷史、土地,以及更重要的,西藏的人民。這個特徵在他的書《西藏:歷史、宗教、人民》當中特別清楚--這本書他與柯林‧滕布爾(Colin Turnbull)合寫(譯按5)。這是一本關於西藏歷史的 美妙百科全書式的記載(特別是民俗史與天文學),他還描寫了藏人的生活,夾雜著各種傳說、神話,以及仁波切小時候、生活與旅行的個人經歷(對歷史書而言是 相常罕見的)。著名的文化人類學家,瑪格莉特‧米德(Margaret Mead),說這本書「獨特、善感而美麗」。

也許有人會說這本書多少理想化了藏人的生活方式。但它從來沒有走到蓄意欺騙或荒謬的程度,然而它清楚地是一種表達,一種象徵,是仁波切對他的人民與他的國 家深層與真摯的感情的呈現。我發現這本書很令人著迷,我甚至在德里買了十幾本,並且在七零年代早期用在話劇團作為高年級學生的英文教科書,也作為教授他們 歷史與文化的入門書。這本書也包含一套民俗藝術家,洛桑丹增的畫作:描繪著藏人的服飾、家用器皿、農業用具、武器、牧民的營地還有帳篷內部,每一張圖都有 編號,旁邊也有說明。這些圖畫本身就是文化的資產。雖然現在連平裝本都已經絕版,旦我想二手書還可以在Alibris或EBay(譯按6)上買到。

前幾天一個朋友告訴我,詩人唯色也寫了一篇有關塔澤仁波切的文章,還提到她是以中國官方的內部翻譯資料,讀到仁波切的歷史書的。我的朋友從唯色博客那裏翻譯了這一段話:

「那本書,我最早看到應是1990年,當時我剛剛回到拉薩,是一個已被漢化得對自己民族的歷史和文化幾無所知的年輕人。那本書, 在我以及境內許多藏人當時的閱讀範圍內,是我們能夠讀到的第一本譯成中文的西藏人寫真實西藏的書。從那時起,那本書被我視為珍寶,走到哪裡都要帶在身 邊。」

當然,仁波切是個很有靈性的人,可能他的靈性非常深邃。他是以僧侶與朱古的身份被教育長大的,而他的書也肯定不是一部世俗的歷史。但與其他西藏喇嘛與格西 不同的是,塔澤仁波切清楚地看到雖然宗教是西藏生活的重要特徵,但只是其中定義藏人生活、藏人身份的多種特色的其中之一而已。仁波切告訴我,雖然他相信他 的弟弟是達賴喇嘛的真轉世,但他並不覺得自己在靈性上很特別。在他的歷史書裏,他坦誠地提到,他作孩子時,面臨朱古的測試,他並不認得擺在他面前的各種物 品。仁波切尤其是一個很誠實的人。他最討厭那些到處聲稱自己擁有特殊的法力修為,事實上沒有,卻利用佛法作為幌子來獲得物質好處的人。他本人拒絕給別人上 宗教的課程。事實上,仁波切把藏學課程裏的必修的宗教課程轉讓給另外一位教授去上。

跟仁波切交談總是很容易。在他面前你不必拘束,在他面前你也從不覺得尷尬,不會不知道是否需要敬禮或磕頭或者得到摩頂。你只是跟他握手,說說笑話,告訴他 從達蘭薩拉傳來的最新閒話。他不會像其他有權力的藏人一樣高高在上。我在九零年代晚期搬到美國後,更有機會與他見面、與他說話。當然我們談話的其中一個重 要主題是讓贊,還有我們如何才能促進那個理想,即使只能發揮很小的作用。

共享讓贊的理想與信念的塔澤仁波切、索南旺堆拉、圖登次仁拉、拉珍哲彤拉、我自己還有其他人,創辦了讓贊連盟。仁波切於2001年11月23-24日在印 第安那的布魯明頓,主持了第一次讓贊連盟的計畫會議。其中兩位(由彼德布朗(Peter Brown)陪同)也開始了橫越二十八州、(加拿大)五省、哥倫比亞特區的讓贊之旅,我們旅行了一個月,並且儘可能地連絡西藏社區、藏人、友人,來重新點 燃一年一年愈亦沉寂虛弱的西藏獨立奮鬥。仁波切寫了一封滿懷熱忱的支持信,我們分寄給每個社區,好向各地的藏人自我介紹,也介紹我們的任務。

當然仁波切也是有缺點的,也不乏批評他的人。其中一個反對他的批評是他遠離了西藏社會,沒有留在達蘭薩拉為流亡政府工作。這樣的指控是有一些道理的,雖然 仁波切曾經是西藏圖書館的館長,也曾經擔任達賴喇嘛的駐日代表。但這些都為期很短。我知道他的某些堯西親戚也因為這樣而批評他,就好像我過去也曾經有過這 樣的批評一樣。

但假如我現在為他辯護的話,我也許會說,他與流亡政府與流亡社會所保持的距離,允許他智識上保持自由,得以繼續堅持獨立的理想。如果他真的為達蘭薩拉政府 工作的話,因為要擔當高位就意謂著必須與政府政策完全同調,我們也許就會有另外一位失敗的協商者:他就會加入嘉樂頓珠、洛迪嘉日等的不知道什麼時候才會結 束的長長名單裏。然而讓贊的奮鬥就會因此而失去一個導師,一個同志。

就因為他沒有留在達蘭薩拉,即使是在美國中西部的曠野裏,塔澤仁波切才有辦法保持「讓贊的火燼」,並且給我們傳達他的信念:西藏獨立是絕對不容妥協的,而且(就像我之前提到的)是西藏人民、西藏語言、西藏文化、甚至他們的宗教續存的一種基本的條件,一種必要的條件。

在2002年晚期,仁波切好幾次中風,行動不便,說話不清。我最後一次看到他是一年以前,他似乎已經認不得我了。然而他還是想辦法跟我們在一起,今年三月 讓贊革命在西藏發生之時,全球各地的藏人都在挑戰共產中國對西藏的佔領。接近仁波切的人告訴我,他似乎知道發生了什麼事情。而且2008年6月的自由火炬 起程典禮上,他也出席了。

仁波切還出席另外一個活動的閉幕典禮,那就是七月四日在費城舉行的自由步行運動。我聽到自由亞洲電台的記者,卡瑪嘉措的錄音,某個人想讓仁波切在該場合上 說一兩個字。當然仁波切因為中風的關係,說話的能力幾乎完全受到影響了,但他十分努力地想要表達什麼。只有兩個音節,非常模糊,一再地喃喃重覆著。聽起來 非常不清楚,但假如你很努力地聆聽,聽起來他好像在重覆兩個音節,「嗯。。。嗯。。。讓-贊。」

譯註1:摩洛甘濟(McLeod Ganji)就是上達蘭薩拉,亦是西藏流亡政府所在地。此譯法乃從「西藏之頁」網站的譯法。

譯註2:史特拉斯堡宣言:達賴喇嘛於1988年訪問歐洲議會時,散發了一份文件,提出「解決西藏問題」的方案。他在裏面提出,由多衛康三區所組成的西藏,應該變成一個自治的政治體,並且與中華人民共和國結盟。而達賴喇嘛將會以放棄獨立的主張來作為回饋。

譯註3:1954-55年,達賴喇嘛在北京期間,時任中共統戰部副部長的劉格平是陪同者。< /span>

譯註4:堯西,歷代達賴喇嘛的家族。

譯註5:Colin Turnbull是英國人類學家,以《叢林人》(The Forest Man)一書聞名。中國大陸翻成柯林‧特呂布爾,台灣亦有譯作特恩布爾者。

譯註6:Alibris與Ebay都是拍賣二手物品的網站。

Remembering the First Rangzen Marcher

Taktser Rinpoche

An urgent voice in Tibetan asked “Jamyang Norbu, Jamyang Norbu, can you hear me. I am Thupten Jigme Norbu.” For a while I couldn’t place the name and then realized it was Taktser Rimpoche, the Dalai Lama’s oldest brother.

— Yes Rimpoche I can hear you, how are you?”

— Jamyang Norbu, Jamyang Norbu, do you know what has happened.”

— What is it Rimpoche?”

— They have given up our rangzen.”

— Rimpoche, what are you saying?

— Gyalwa Rimpoche made a statement at this place, Strasbourg…”

And he told me what had happened.

I am not on terms of any real intimacy with members of the Dalai Lama’s family, and it took me a little while to figure out why Taktser Rimpoche had contacted me. It probably had to do with my writings in the Tibetan Review, where I had been regularly analyzing and condemning the Tibetan government’s policy of downgrading Tibetan independence to conciliate Communist China. My last contribution had been a two-part article (“On the Brink”, Oct-Nov1986) warning of the increasing Chinese population transfer into Tibet. I stressed that the only way to deal with this crisis was not to appease Beijing but to actively discourage business, tourism and investment in Tibet. Destabilize the region. In those early years of Deng’s liberalization there was an opportunity to do something like that. Officialdom, of course, ignored my report. A couple of inji readers accused me of sabotaging the wonderful new relationship between the Chinese and the Tibetans.

“And what are you going to do?” Rimpoche asked me at the end of the conversation.

What could I say? I told him I didn’t know; that I wasn’t in any position to do anything.

I think I disappointed him with my answer, but that conversation started a friendship, nonetheless. There was, on both sides, a bit of emotional dependence in this relationship. Those who espoused the cause of independence became increasingly marginalized in exile society and accusations of “opposing” the Dalai Lama were readily hurled at those who expressed any doubt at the Middle Way approach. So even if you happened to live at the opposite ends of the earth, you took strength in the friendship, no matter how long distance, of those few Tibetan who would not give up rangzen.

Rimpoche wasn’t a spring chicken then, in fact he was 73 when with the help of Lawrence Gerstein he founded the International Tibet Independence Movement and led a number of independence walks that took him all over the United States and Canada. I was back in Dharamshala during those years, editing the Tibetan newspaper Mangtso. It was always an uplifting experience to see a photograph of Rimpoche on one of his marches, striding vigorously, his white baseball cap tilted back on his head, telling America that Tibet was an independent country and that Americans had to support the cause.

He always seemed to make his statements with a big smile. Rimpoche wasn’t one of your grim, teeth-gritting nationalists. His conviction regarding rangzen did not come from any hatred of the Chinese people or some ultra-patriotic doctrine or philosophy, but merely that he had no illusions about China’s real intentions regarding Tibet. Rimpoche was convinced that Tibet needed independence not for some exalted ideological reason but as a fundamental condition, an essential requisite for the survival of the people, their language, their culture and even their religion. Rimpoche was certain there was no other way.

I feel Rimpoche had this clarity in his thinking because the Communist leaders he first encountered in Amdo, when he was abbot of Kumbum monastery, were the real deal: crude, self-righteous, devious and murderous men — de-humanized progenies of the unbelievably savage Chinese Civil War. Rimpoche describes them very accurately in his autobiography Tibet is My Country. Left wing propaganda a la Edgar Snow has left us the impression of Chinese Communist cadres and officers as idealistic agrarian reformers with a soupçon of the Taoist sage about them, but anyone who has some idea of the history of the Chinese Communist party will be aware how many in the Red Army were ex-warlord officers, mercenaries, former bandits, ex-junkies and the like. Rimpoche also witnessed how the Communists dealt with opposition when they wiped out the Muslim Huis of Lusar, close to Kumbum. Rimpoche was also in Amdo when the Red Army slaughtered the Amdowas of Nangra and Hormukha and started their genocidal campaign against the Goloks.

In Amdo the Communists do not appear to have tried to win over people with guile and sweet-talk. Most probably they felt that Qinghai was theirs anyway, and they didn’t have to bother. The outcome of their invasion of Tibet, on the other hand, was far from certain, and the Communists were careful that their representatives in Lhasa and Chamdo were outwardly pleasant, smooth-tongued people.

The first Communist officials that His Holiness the Dalai Lama met and interacted with in Tibet were attractive and charming equivocators like Baba Phuntsog Wangyal and Liu Ke Ping the ideologue, both of whom taught the Dalai Lama Marxism-Leninism, the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union’s nationality polices. Phuntsok Wangyal mentions in his autobiography that “The Dalai Lama was very eager to learn about all aspects of communism, and I think we had an effect on his thinking. Even now, he sometimes says that he is half Buddhist and half Marxist.” We should bear in mind that His Holiness was very young, in his formative years and impressionable. His long held belief, that he could arrive at some understanding with the Chinese leadership on the question of Tibet, has probably been shaped to a degree by this early experience.

But Taktser Rimpoche’s was a grown man, thirteen years older than His Holiness, and his experience with the Communists convinced him that China’s intentions regarding Tibet were malevolent. Rimpoche was not without some guile himself, and he managed to give the impression to his captors that he was receptive to their overtures. They decided to send him to Lhasa to win over the Dalai Lama. Rimpoche describes the unbelievably crude way the Communist leaders approached him promising to appoint him “governor-general” (chikyap) of Tibet if he convinced the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government not to resist the Chinese advance into Tibet. They even went so far as to hint that if the young Dalai Lama got in the way he could be taken care off, and that Rimpoche might think about it doing it himself “…in the interest of the cause”.

Rimpoche reached Lhasa on the eve of the invasion and told his brother everything. His advice probably contributed to the young Dalai Lama and the Tibetan cabinet’s decision to leave Lhasa after Chamdo had fallen. When the Tibetan government and the Dalai Lama chose to remain temporarily in Dhromo in the Chumbi valley, Rimpoche decided to continue on to India. Once in India his old friend Tilopa Rimpoche (the Dilowa Hutukhtu) contacted him. He told Taktser that arrangements had been made through the Committee for Free Asia (a CIA front) for him to travel to the United States. This eminent Mongol Lama, who had survived Stalin’s purges, had been invited to the United States in 1949 as a resident scholar at Johns Hopkins University. The American who made this possible was the distinguished orientalist, Owen Lattimore, who was then a key consultant of the United States State Department’s Far Eastern affairs. It is ironic that someone who aided this Mongol lama and (indirectly) Taktser Rimpoche to escape Communist persecution should later became a principal target of Senator McCarthy’s infamous anti-Communist witch-hunts and face false charges of being a “top Soviet agent”.

Rimpoche didn’t have an easy time of it in the States, what with bad health, lack of English and insufficient funds. But he gradually learned English (at Berkeley) and even mastered Japanese when staying in a Japanese monastery for some years when the Government of India did not renew his expired IC and the American government was not helpful about giving him asylum. The CIA had lost their initial interest in him after the Tibetan delegate in Beijing signed the 17 Point Agreement and the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa. Finally, after about three years his friends in the World Church Services secured permission for Rimpoche to return to the United States. He earned a modest income giving Tibetan classes to a handful of students as a part of a non-credited course at Columbia University, while his servant Dhondup Gyaltsen worked in a factory. I got the impression from his autobiography that Rimpoche spent his evenings in his small New York apartment making soup (most probably thinthuk soup) “…according to a typical Tibetan recipe”

This was at a time when Tibet was having its honeymoon period with the Communists and many merchants, lamas, monasteries, aristocrats and yabshi were reveling in the dayuan silver the Chinese were spreading around Tibet. Many of Rimpoche’s old acquaintances tried to convince him to return to Tibet including some of his own relatives, as he frankly mentions in his biography. But Rimpoche was convinced that the easy money and strident affability offered by the Communists was a passing phase and that there would be a reckoning soon. His younger brother Gyalo Thondup who had studied at a Guomindang school in Nanjing was also distrustful of the Communists and escaped to India from China.

When the Dalai Lama came to India in 1956 for the Buddha Jayanti celebrations, Rimpoche immediately flew to India where with Gyalo Thondup he tried to persuade his brother to seek asylum in India. Other Tibetan leaders in exile as the former Prime Minister, Lukhangwa, pleaded with the Dalai Lama not to return to Tibet. But in the end the Dalai Lama consulted the state oracle. The Dalai Lama mentions in his Compassion in Exile that Lukhangwa refused to leave the room even when the oracle became angry with him. The old aristocrat warned the Dalai Lama “When men become desperate they consult the gods. And when gods become desperate, they tell lies.” But the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa.

A disappointed Taktser Rimpoche flew back to New York. By this time, fighting had broken out all over Eastern Tibet and Rimpoche was in regular communication with the State Department. He had also re-established his contacts with the CIA. In an interview he gave me he said that he later passed on all these contacts to his brother. He did not explicitly say so but I assumed he must have realized that Gyalo Thondup had the more conspiratorial bent and the diplomatic skills necessary to use these connections effectively to benefit the Tibetan cause.

Rimpoche assisted in the training of the first group of Tibetan agents (Athar, Lotse, Gyato Wangdu and others) in Saipan, acting as an interpreter. Rimpoche along with the Kalmuk Geshe Wangyal were also on the CIA team that devised a telecode system to describe items that were not in the Tibetan vocabulary and created a system of writing precise intelligible messages concerning modern warfare and intelligence, within an archaic traditional language. Rimpoche and Geshe Wangyal were also involved in the writing of training manuals for guerilla warfare, sabotage and so on.

Rimpoche’s language skills: Tibetan, Mongol, Japanese, Chinese, English and his native Sining patois, underscored his essentially scholarly nature, and he probably found the whole warfare and espionage world alien to his nature. He went back to his teaching, but he also started to organize relief effort for Tibetan refugees with his contacts in the World Church Services and other organizations.

Rimpoche initiated Tibetan studies programs at the American Museum of Natural History and also developed a similar program at Indiana University, where he received a professorship. He began teaching there in 1965 and as an old student of his told me “he had no trouble drawing students to his classes”.

What I have always found intriguing about this high lama, abbot of one of the most important Gelukpa monasteries, and a brother of the Dalai Lama, is that he was not interested in giving dharma lessons or starting a dharma centre, but instead wanted to let the world know about the culture, the history, the land and most of all the people of Tibet. This trait comes out clearly in his book Tibet, Its History, Religion and People, which he co-authored with Colin Turnbull. It is a wonderfully encyclopedic account of Tibetan history (especially folk history and cosmology) and Tibetan life, studded with all manner of legends, fables and (unusually for a history book) personal and intimate memories of Rimpoche’s own childhood, life and travels. The well-known cultural-anthropologist, Margaret Mead, called it “a uniquely sensitive and beautiful book”.

It could be pointed out that the book somewhat idealizes Tibetan life. But then again it never carries it to a point of dishonesty or absurdity, and is clearly an expression, a metaphor, for Rimpoche’s deep and genuine feelings for his people and country. I found the book so enchanting, so irresistible that I bought a dozen or so copies of the paperback edition in Delhi, and used it at TIPA (in the early seventies) as an English textbook for senior students, and as a primer for teaching them their history and culture. The book also had a wonderful set of drawings by the folk artist Lobsang Tenzin, of a variety of Tibetan costumes, household utensils agricultural implements, weapons, nomad encampment, and interiors of tents with everything numbered and identified. It was a cultural resource in itself. Even the paperback edition is now out of print but I think second-hand copies of the Pelican edition can be bought on Alibris or EBay.

Just the other day a friend of mine told me that the poet Woeser had written about Taktser Rimpoche and mentioned that she had come across Rimpoche’s history book in an official neibu translation. My friend translated this excerpt from Woeser’s blog:

“The first time I read the book was probably 1990. At that time I was newly returned to Lhasa: a sinicized youth, who knew almost nothing about her own people’s history and culture. In my circle and in the reading circles of quite a few Tibetans in Tibet that was the first Chinese translation of a book in which we could read about Tibetans and about the real Tibet. From that time on I regarded the book as a treasure; wherever I went I kept it by my side.”

Of course, Rimpoche was a spiritual person, perhaps even deeply so. He had been raised a monk and a trulku and his book is definitely not a secular history. But unlike many other Tibetan lamas and geshes, Taktser Rimpoche clearly saw that although religion was an important feature of Tibetan life, it was only one of the many features that defined the life, and indeed the identity of a Tibetan person. Rimpoche told me that although he firmly believed that his brother was the true incarnation of the Dalai Lama, he did not consider himself to be a special person spiritually. In his history book he candidly mentions that as a child he did not recognize any of the objects placed before him when he was tested. More than anything Rimpoche was an honest man. He absolutely detested those who went around claiming spiritual authority and accomplishments that they did not possess, and exploited the dharma for material gain. He himself refused to give religious teachings. In fact Rimpoche delegated another professor in his department to teach the required course on Tibetan religion for the Tibetan studies program.

It was always easy to talk to Rimpoche. You didn’t have to stand on ceremony with him. You never felt awkward around him, unsure whether to bow or prostate or receive a chawang. You just shook his hand, made a joke, or told him the latest gossip from Dharamshala. He also never patronized you like the great and powerful in Tibetan world generally like to do. I got to meet him and speak to him more often after I moved to the States during the late 90’s. And of course one of the main topics of conversation was rangzen and what we could do to promote the ideal, even in a small way.

1st Rangzen Alliance Planning Meeting: Lhakpa Tsering, Thupten Norbu, Jamyang Norbu, Elliot Sperling, Lhadon Tethong, Thupten Tsering, Lisa Keary.

Rimpoche had his faults, of course, and his share of detractors. One of the usual criticisms against him was that he had stayed away from the Tibetan world and had not worked in Dharamshala for the exile government. There was some truth in that charge, although Rimpoche served (very briefly) as the Director of the Tibetan Library and as the Dalai Lama’s Representative in Japan. But these were short stints. I know that some of his yabshi relatives also held that against him, as in fact I did for some years.

But if I were to argue on his behalf now I might say that the very distance he maintained from the exile administration and exile world, allowed him the intellectual freedom to hold on to the ideal of independence. If he had served in Dharmshala, where absolute conformity is the minimal requirement for holding any kind of high office, we might have another failed negotiator in the long list starting with Gyalo Thondup and Lodi Gyari and ending with God knows who. But the rangzen struggle would have lost a mentor and a comrade-in-arms.

As is it is, even out in the wilderness, the yul-thakop of the American Midwest, Taktser Rimpoche was able to keep alive “the embers of rangzen” and pass on to us his conviction that Tibetan independence was absolutely not negotiable, and was (as mentioned earlier) a fundamental condition, an essential requisite for the survival of the Tibetan people, their language, their culture and even their religion. There was no other way.

In late 2002 Rimpoche suffered a series of strokes and became an invalid. The last time I saw him a year ago he did not appear to recognize me. Yet somehow he was still with us, when in March this year the rangzen revolution happened in Tibet, and Tibetans everywhere around the world challenged Communist China occupation of Tibet. People close to Rimpoche told me that he did seem to appreciate the significance of the events. And at least his presence was there at the Freedom Torch reception ceremony in June 2008.

Rimpoche was present at the conclusion of another event, the Freedom March in Philadelphia last Fourth of July. I heard this recording made by a Radio Free Asia correspondent, Karma Gyatso, where someone was trying to get Rimpoche to say a word or two for the occasion. Of course Rimpoche’s speech had been near completely impaired by the stroke, but he made a great effort to say something. It was just two syllables, very indistinct, murmured again and again. It was not at all clear, but if you listened hard, it seemed like he was repeating these two syllables “hrrm-hrn … hrrm- hrn … rang-zen.”